Ideally, you would focus on doing just one thing; do it; then move into doing something else. But in the end, you find so many distractions. Tasks take longer to do than expected. Things get post-poned for tomorrow, for next week, or for never.

Again and again, what happens is not that we don’t have time to do stuff, is that we want to do more stuff than we can. What else would you be able to do if you renounce to non-important things?

Close to finish what you are currently reading? Take a look at a few books that—in some way or another—changed my life.

Over the last years, I have been lucky enough to find a series of books which helped me getting introduced to organization methods and learning how to work on my own projects in a consistent way. (A project could be any life-goal you set for yourself to do.)

Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity by David Allen. Allen presents a powerful way to manage and organize the tasks and projects you want to complete—how to get things done, basically—in order to have a good work-life balance. Get it on Amazon.

Making Ideas Happen by Scott Belsky. Techniques and work habits to make your creative projects happen. From the creator of Behance. Get it on Amazon.

Unclutter Your Life In One Week by Erin Doland. Even the most common sense tasks of your daily life—as can be organizing your clothes or getting rid of physical clutter—can benefit from fire-proof methods tested by others. In this case, Erin Doland provides a handful of them. Get it on Amazon.

All Marketers Are Liars by Seth Godin. A swift introduction to marketing. How to wrap what you have to offer around a story so it can be understood and spread by others. Get it on Amazon. Read Seth’s blog.

The Art Of Non-Conformity by Chris Guillebeau. Go away from the life you are supposed to live and enjoy an unconventional way of living doing what you actually like doing and, maybe, making a profit out of it. Get it on Amazon.

The 4-hour Workweek by Timothy Ferris. Change the way you see life. Get to know the new rich, the one that makes the amount of money needed for the way of living he really wants—but not more—being able to work less hours as a result. Get it on Amazon.

Hope you found this useful. I strongly believe that, even when books tell us things that are damn simple and obvious, advice from people who learned the hard way, after years of experience, is extremely valuable. No matter how basic their recommendations are, they are useless if we don’t make an effort for them to be present in our daily lives.

We all know "the right thing to do," but do we actually do it?

(Image via)

August 12, 2015. I was on holiday in my hometown, Málaga, south of Spain. The summer was a transition between living in the United Kingdom to living in the United States—to disconnect and sort out a fair amount of paperwork I had to do before leaving.

That day, I had an appointment to renew my Passport at the police station. That was all I would worry about that morning. I got inside the building, said my name at the front desk, and heard the magic words: "Please, wait here."

And there I was. I had been given a precious gift. A few minutes or, maybe, half an hour, when all I could do was just sit there and wait for my turn. A span of time in a context you would never decide to be on your own, but now you have been forced to. All you have to do is sit there and do nothing.

It is a precious moment for yourself. A moment when you can think. You can empty your mind. You can write. You can listen to music. You can do nothing.

We are all busy. We are definitely doing something wrong.

We have more things to do today than we could do in a whole week. More often than we’d like to, we produce things and forget we have to "sell" them.

It does not matter how good what you create is, the need to market it is always there—people need, somehow, to know about your product. There is no way they can give it a chance if they don’t even know it exists.

Along the same lines, you need to let them know what you are up to. No matter what you are doing, it is extremely important to **give your potential customers a way to keep track of what you are working on—**especially if what you are pursuing is to build a tribe, a community. May it be a mailing list (which you should already be rolling out), an RSS feed, or a social media account, your users must have a way to follow your work, one that they are comfortable using already. The best case scenario is, probably, a combination of all of those mentioned, so the user can choose how she'll be hearing from you.

It’s one of my biggest business mistakes, not setting up an email list for several years. —Ramit Sethi

Giving people a way to know about what you are doing is key to any activity that relies on a tribe. Even more important, is providing users who value your product with ways to pay for it. Remember that store that couldn’t take your money because they didn’t accept payments by card? The worst thing you can do is having users willing to follow and pay for your work and not letting them do it.

This essay is part of the book I am writing on how to organize your life in order to create more and better. If you want to receive new parts of the book as I write them, please join here, and check other posts that will be on the book.

There’s a myth that time is money. In fact, time is more precious than money. It’s a nonrenewable resource. Once you’ve spent it, and if you’ve spent it badly, it’s gone forever. — Neil A. Fiore

Essentially, time isn't money. You will never recover the time passed. We find it difficult to frame our lives this way. Money spent can be recovered and it will, maybe, free up slots of time in our busy schedules, but it won't—ever—buy us more time.

As a reminder, Frank Chimero sums it up in two short sentences.

Money is circulated. Time is spent. — Frank Chimero

—

This essay is part of the book I am writing on how to organize your life in order to create more and better. If you want to receive new parts of the book as I write them, please join here, and check other posts that will be on the book.

While reading Vagabonding by Rolf Potts, I found this quote—penned by William Morris, an influential designer, writer, and socialist of the nineteen century—which summarizes what minimalism is in terms of physical belongings.

Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

Everyday, many of us struggle to achieve our goals. Those goals may be simple things we thought of doing, important documents we have to submit, or things we want to try that end up never happening.

People often ask me: How do you find time to do that? or When do you work on that kind of stuff? I don’t have time.

The first thing that comes to mind is that I don’t have time usually means it wasn’t important enough.

Well, it is probably true. Not getting something done means that, after all, it was not as important as it seemed—or that it was not urgent—so you didn't do it. The thing is, that even when you consider something important and urgent, you need time get it done, time to get your hands dirty.

What works for me—and for many others—is to write down the things you really, really want to do on an actionable list and take your time seriously.

Decide what it is you want to focus on the next time you sit down to work. Make your projects a part of your life—no matter if your plan is to spend time exercising, writing, or learning Chinese. When you have a clear idea of what projects you want to focus on, you will know what to do when you have time for it. Then, ruthlessly ignore everything that does not contribute to move the ball forward to your goal.

After deciding what to do, you need to convert those things-to-do into actionable steps. For instance, instead of Learn Chinese, your to-do list should split the project of learning Chinese as: Search for a Chinese course; Sign up to a course that fits my schedule; Study Chinese; Do homework.

Notice how every task in your list starts with a verb, an action you need to perform to fulfill the task? It's important to follow this structure, so when you read the task in the future you can directly take an action to complete it. If you want more detail, see this post.

This to-do lists seem so silly for many people, who think that just by knowing what they want to do, they will. Wrong.

When you have a 30-minute break, or an unexpected free morning, or a whole day to do stuff, it is way too easy to waste your time doing nothing (you have to consider what wasting time means for yourself, as nobody else can do it for you). Some people may consider productive spending the afternoon watching movies or series, while others may rather write, paint, or exercise instead.

In these dead moments is when your list comes into play. Like a message in a bottle, you can message your future-self with a set of things you intended to do.

Maybe, you wanted to go for a run, or to write an article, or to email required documentation to your real state agent, or to spend more time with your family. The thing is, you don’t have to think on what to do, you can just choose among a set of things that, apparently, you want to do, and are written down in your list.

One day, you will embark an 8-hour flight back home. Your to-do list will remind you of one thing: an article you wanted to write, a document you wanted to read, or some other thing you are curious about. You will get hands on it and, maybe, will get out of the plane with one more thing done.

—

This essay is part of the book I am writing on how to organize your life in order to create more and better. If you want to receive new parts of the book as I write them, please join here, and check other posts that will be on the book.

Is it when we get old that we gain experience?

Is the act of doing the only way to forge it?

Do you need to be employed by someone to acquire skill and knowledge?

Experience. noun. the knowledge or skill acquired by experience over a period of time, especially that gained in a particular profession by someone at work.

Experience is obtained by doing. It may be doing stuff at work or doing stuff at home. Doing work for your boss or doing work for yourself. It is all experience. The more you practice an activity, the more experience you get.

By being constant and consistent; by learning from other people's stories; by getting feedback on your work and finding ways to implement it in the future. That is how we obtain knowledge and skill. That is how we gain experience.

You cannot create experience. You must undergo it. — Albert Camus

Picture a person who wants to get really good at public speaking. The only way she can get better at it is by doing that activity. By speaking—a lot—in front of people. By interiorizing techniques and reading what professional public speakers do will probably help her be more confident and feel the situation is under control. It may provide knowledge, but it won’t provide skill. The key part is the act of speaking in front of an audience: Practicing.

I believe in experience as the result of combining both hard work and consistent efforts over a period of time; becoming better at something by doing, and by constantly learning from yourself and from others. This doesn’t necessarily imply you won’t learn anything by reading other people’s experiences, but, surely, it won’t get the job done.

Experience can be accelerated. Different people may reach different grades of experience, depending on how good they are at something, and how much time they put on it. Experience can be accelerated by forcing ourselves to do more.

You don’t need experience. Experience can sometimes get you in the door, but what really matters is where you are now and where you’re going next. The past belongs on a resumé. — Chris Guillebeau

In an ever-changing world, the task of finding a job to get real-world experience can be challenging. As Chris Guillebeau questions on The Art of Non-Conformity, experience may not be that important after all—as nobody knows what they are doing.

The exciting part is, we have today the opportunity to acquire knowledge and skill in almost any field on our own. Take your laptop. Take an online course on iOS programming. Make an app. If you learn from an online or offline resource on your own, build something, and ship it, that is real-world experience.

This is, I believe, why many young entrepreneurs have succeeded early in life—and you can do too—working under their own terms. By practicing, reading, learning, executing, and shipping, they have imbued themselves into real experience.

—

This essay is part of the book I am writing on how to organize your life in order to create more and better. If you want to receive new parts of the book as I write them, please join here, and check other posts that will be on the book.

As we continue adopting new digital services and embracing new technologies, our [digital] lives gain more and more complexity. Everything we use gathers data, stores the content produced with it, and, in many cases, learns from the way we behave.

Information, content, reports, and other kind of media conforms a big compound of data, which is often difficult to manage.

How are we expected to handle this situation? How are we supposed to properly manage systems that were not even invented when we were educated? And even worse, how is people expected to teach us about things they have never used? I firmly believe that this will affect our generation, too. We feel like we have the situation under control; just give it a few years until new services, new technologies, and new things are released.

Digital tidiness should be a subject at school. Everyone needs to be able to correctly manage digital clutter.

But there are surely ways to work that may ease the pain. Defined workflows can be implemented in our use of digital systems. The same way we use workflows in our daily tasks outside the digital realm to tackle everyday problems, we can use them in the digital world.

The process you follow when you bring new things into your room: arranging your belongings and your clothes; trashing out old stuff you no longer need, is, for instance, a workflow implemented in your life.

With the same ease digital services allow us to store and manage our data, they become a mess of unmanageable things.

Digital tidiness should be a subject at school. Everyone needs to be able to correctly manage digital clutter, as everyone needs to know how to arrange their clothes, to keep physical documents in place, or to find their belongings when needed.

Every once in a while, I find myself arranging clothes or belongings and giving away things I do not want anymore—archiving and deleting, basically. At times, stuff is just too much to be handled, or there is no time to invest on the task.

The amount of data produced should be limited according to how much can be processed and stored.

The same problem exists in electronic devices and digital storage system. When we produce more content than we process, we are leaving behind a lot of things that would have to be done in the future. For that reason, apart from organizing all our data, we need to be conscious of how much stuff we can handle. The amount of data produced should be limited according to how much can be processed and stored.

One concrete example is taking digital pictures. Thanks to flash-memory-powered DSLR cameras, giga-sized internal capacities of our portable devices, and on-the-go cloud storage services, pictures and videos can be taken daily with no limits. The problem is, these instant task will later take an enormous quantity of digital space and an immeasurable amount of time to process and organize.

Workflows can help reducing the processing and organization time, but awareness of how much is produced is equally or even more important than post-processing. Do you really need to take that picture? Maybe not.

Creating a plan to make a difference is easy. Sticking to the plan—and adopting it as a habit—isn't.

That's the difficult part—the reason why not everyone will succeed in the long run.

Think of what you want to do. Commit to it. Set deadlines. Involve others in the process. Do at least ten minutes of it every single day. Make the habit.

This essay is part of the book I am writing on how to organize your life in order to create more and better. If you want to receive new parts of the book as I write them, please join here, and check other posts that will be on the book.

It is in our nature. We have a need to produce stuff. It does not seem to matter what it is that we produce, the important part is producing something. The judgement of others, or even our own judgement, is the reason why what we produce gets to be important, and how good the result is, leaving aside the process more often than we should.

In a world with so many talented people, high expectations freeze people. They stop people from getting a pen. And just because they know somebody else has, will, or is doing something better than them, somewhere else. But that is wrong. If you did not even try, how are you so sure your stuff is not better? Or, does it even matter if it is? I don’t believe so.

What you are willing to produce may have been done before, but your personality will always add a bit of originality to anything you do.

Frustration, though, comes due to the fake need to produce more and more, caused by our era, the digital. The Internet moves so quickly that when you clarify your concept, someone else has already funded the idea on Kickstarter.

The key: understanding there isn’t such a need to produce more and faster, but to produce wiser and better.

The concept of the new rich was coined by David Moore's book, and also explained by Tim Ferris in The 4-hour Work Week, as a response to the way many people configure their lives nowadays. The term defines a new kind of person—one that has enough money to do what she planned to do, but no more than necessary.

It also means that the person has built some kind of framework around her life in order to keep things going. Just the amount needed in case things go wrong.

This person knows that life is to be enjoyed today—not tomorrow—and believes in money as a mean of being able to achieve things today, as-we-go, and not to lie in a tomb whenever we die with gold, useless belongings, and other stuff accumulated over the years.

Of course, living today is risky; the “amount needed” to be out of danger will never be clear; and the safe zone is a comfortable one. But it seems it is worth it, because, who can assure you will be able to enjoy tomorrow?

More and more, online services are making their best to provide free services in exchange personal data [trust, and habits].

The currency used to pay this services—like Facebook, Twitter, or Google—is private data, which turns out to be, pretty often, really sensitive information.

Everytime you click an ad on Google, a hashtag on Twitter, or content on Facebook, you can expect to be bombarded with similar content on the future, with related products to buy, or with brands that advertise specifically on the terms you searched for.

Gently lent your computer to a friend who had to look for flights to China?

Expect a lot of ads with sales to fly to China in many other pages.

It is when we see this kinds of things that we realize we are actually being tracked with a purpose. Have you ever regretted a click? I have.

Sometimes, magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect. — Raymond Joseph Teller

If what you do is not on the mainstream movement of its discipline or category, your public is a minority—one that may be interested in the same things you are. That minority is formed by the ones who may listen to what you have to say—but reaching their attention is no easy job.

I do not expect everyone to read what I post, nor do I expect everyone to be interested on the same things I do. I hope that those who are [interested] will come back to read more of what they liked, and will be the ones sharing what I write with their friends.

Focus the work you do on what you like doing, and make it understandable for everyone. The ones who want to listen will slowly discover your work and, hopefully, will come back to see what’s new.

Frequently, what you need is not changing what you do to find new public but reaching the people who like what you already do.

Is to leave them aside. To be connected to them—as a sketcher to her pencil or a painter to her brush—so the tool fades to let the creative focus on the design, instead of getting lost on the tools.

Knowing what you can do with each tool is essential to create. Otherwise, time disappears trying to master a tool rather than creating with it.

Knowing when to go back to pencil and paper—and concentrate in ideas—is important too.

A friend of mine is going to get a new MacBook Pro soon. Depending on the conversation, he frases his incoming acquisition in two different ways:

I am going to buy a laptop which has a Retina Display, an Intel Core i5 processor, and a 1-terabyte SSD drive, or;

I am going to buy a laptop that will allow me to write, code and design stuff I like—in a better way than I do now.

Everything we experience is seen through a lens—a moldable and adaptable lens. Somehow, we choose what we see through it.

Defining your world with facts and figures—as happens in the first example—allows to quantify how much time, money or effort a given life-change is going to cost.

On the other hand, perceiving the world with stories leaves figures aside and lets the subconscious decide for you, as it wants you to be that person writing, coding and designing—with a tool supposed to give you a better experience.

This is, in many cases, the reason why people buy expensive things. They tell themselves a story, one that creates an ideal world, achievable if they have that thing, no matter if it's a new house, a new laptop or a new pen. Also, it is the reason why people keep drinking Coke. Coca-Cola does not advertise a drink, they sell happiness.

Making it easy for people to create and share their own stories about your product is—with no doubt—a key factor if you want them and their friends to use it.

People who say it cannot be done should not interrupt those who are doing it. — George Bernard Shaw

Make. Share. Try. Get things done. Mute interruptions.

Why is it harder to commit to oneself [and make a living with your own work] than working for someone who pays you?

When there is no guaranty your work will cover your fees at the end of the month it is complicated to employ your time working on it.

Solo-work is hard. It requires discipline, willpower, and commitment. If nobody is watching, it is so easy to get trapped in the incoming flux of social media, email, and other distractions, letting the time go without getting anything done.

Freelancing and remote work, on the other side, bond you with a contract to a client. You are responsible to fulfill the needs of the person who ensures you will be paid. This responsibility makes it easier for you to invest your time on the work.

The key point is then finding how to enforce ourselves to create a bond with our work without having a client at the other end. Commit to your public, to your users, to the future clients of your product. Look for ways to motivate yourself and make things happen on your own, without being tied to anyone. It is possible.

Success is waking up in the morning, whoever you are, wherever you are, however old or young, and bounding out of bed because there's something out there that you love to do, that you believe in, that you're good at; something that's bigger than you are, and you can hardly wait to get at it again today. —Whit Hobbs

It does not exist. Or, at least, you have no way to know it while you are doing it.

Do not put that much effort. Take decisions quickly, and ship things often.

Every project should be considered important, but it is important to finish and release them. And then, afterwards, polish them—as they are being used by your intended users.

A book is not complete until there is people reading it. A website is undone if users can’t browse it. A product is not finished until clients can pay for it. What is left in your project until it is ready for its public?

Seems crazy to me how easy it is to focus when accessing the Internet is just not there. The train without Wi-Fi gives you a span of precious time. Compared to office hours, the minutes you spend on the train are a gift to do something different.

Forcing ourselves to disconnect and create those moments is not that easy. Your brain gets bored of doing stuff after a while, and the one-minute-visit to Facebook quickly kills your 30-minute potential creative gap.

—

This essay and The Call Receptor were written in a train from Madrid to Málaga in just 20 minutes. No email, no Facebook, no Twitter.

Projects, projects, projects. More projects.

Which of your current activities would endanger your long time goals if you stopped doing them? Those are the important things in your life.

In addition to important projects, are side-projects. Projects as personal research in fields where you want to practice deliberately or learn new stuff on your own. These are projects that won’t bring you money in the short term and won’t affect your long time goals if you kill them.

To make things work, our overhead needs to be kept low, setting a focus on our main projects and responsibilities. But side-projects are also necessary; Small projects to procrastiwork with each once in a while and disconnect from our main duties.

Make clear which of your current projects are important to focus on them, and which ones should be worked on the side.

People never want to be part of the process, but they want to be part of the outcome. The process is where you figure out who´s worth being part of the outcome.

(via)

Every new cloud service we embrace and implement in our lives becomes a new place to store garbage.

The work of keeping things tidy in the digital world is as difficult —and sometimes even more— as physical clutter.

The only solution: keep it simple. Close accounts from services you don’t use anymore and store your stuff in the ones you use the most.

I firmly believe that organizing the digital realm should be taught in school. Many of us believed in the organized disorganization as a valid method, but it is not. I realized how good some habits are after reading Getting Things Done by David Allen.

There is proof of the benefits of being organized that also apply to cloud services and electronic devices.

Backup management, folder organization and cloud storage are aspects which require discipline and a structured use in order to keep everything tidy on-the-go.

Adopt systems of your own or systems which have been created and tested by others, but don’t be naive and think that bad management won’t affect your productivity.

If you are thinking on doing something and sharing it with the world, it is worth while to read the following from Seth Godin:

You might be waiting for things to settle down. For the kids to be old enough, for work to calm down, for the economy to recover, for the weather to cooperate, for your bad back to let up just a little...

The thing is, people who make a difference never wait for just the right time. They know that it will never arrive.

Instead, they make their ruckus when they are short of sleep, out of money, hungry, in the middle of a domestic mess and during a blizzard. Whenever.

As long as whenever is now.

Nothing will tell you when is the best moment to do something, or when that thing has reached perfection. Over analyzing flaws will stop you from shipping. Also, the way you value a product is different from how other people who do, as not everyone understand the world as you do.

What are you waiting for?

Get your product out now. Just ship it.

An app, a beer, a song, a burger. The list could go on forever.

Some of the things we get are ephemeral, others are permanent —or at least less ephemeral. If you have to pay $2,99 for a song, you would probably think about it. But paying $2,99 for a beer when your are out with your friends is reasonable.

The beer is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, while the song will be yours forever.

Same thing happens with an app (at least in the App Store) — where once you buy a product you can get future uploads for free.

What has more value?

This article was written for us. To organize the work of the projects I am currently involved in. To make them more effective. The following are definitions of three strategies we are going to test in the incoming months.

Stories help up spreading ideas. Explaining concepts is a lineal process suitable to be compressed in a talk.

A talk empowers the speaker to be concise, to highlight the important, and to clear up the ideas to be transmitted.

Concepts, projects, ideas. They all can be formalized as small talks, bits of organized and synthesized content to be spread easily, giving a speech or sharing a couple of slides.

Everything has a by-product. — Jason Fried

In the digital era, a vast amount of content is produced daily, often with a defined purpose.

Spending a bit of time looking for extra possible uses —even before creating— can multiply the effectivity of creating something, and increase your productivity.

A by-product is the result of using a product for a purpose different than the one it was originally created for.

This leads to the next point: passive income.

Passive income is the opposite of active income. It involves obtaining money without having to constantly interact with the content, as you already created it and it is in a place where people can pay for it.

Passive income can be generated in different ways. Writing a book, creating an app, designing icons, taking pictures, or creating templates, are some examples.

Contrary to directly selling your products to customers, distribution is usually done by someone else, who gets a share of your product. For instance, the App Store and the iBook Store retain thirty percent of the income generated with your apps and books, and frees you from setting up your own server to distribute and sell content.

On the lines of working towards by-products, a passive income framework is a powerful tool. Your content, created for some other purpose, can be available for sell online.

A passive income framework consists in organizing —before production— where and how will your by-products generate income.

There are different mediums in which content can be distributed online to generate passive income, as I will show in an incoming article.

Thanks for making it so far. Hopefully you find ways to apply these strategies to the work you are already doing. If you do so, I would like to hear about it.

This post was started on April 2nd, 2014. Two months away from submitting my final project to become an Architect, I wrote this:

I can not post helpful information, as I do not yet know if the process I am following is going to have a positive outcome.

With this, I meant that I would wait to share any suggestions on how to manage your time and resources to do your project after testing if it worked for me.

Now —knowing it worked for me— I am sharing it with everyone who wants to hear because, used properly, this advice can be really helpful.

I want to emphasize that I am not sharing architecture design tips here, but ways to organize creative projects and be efficient in order to finish and ship project on time.

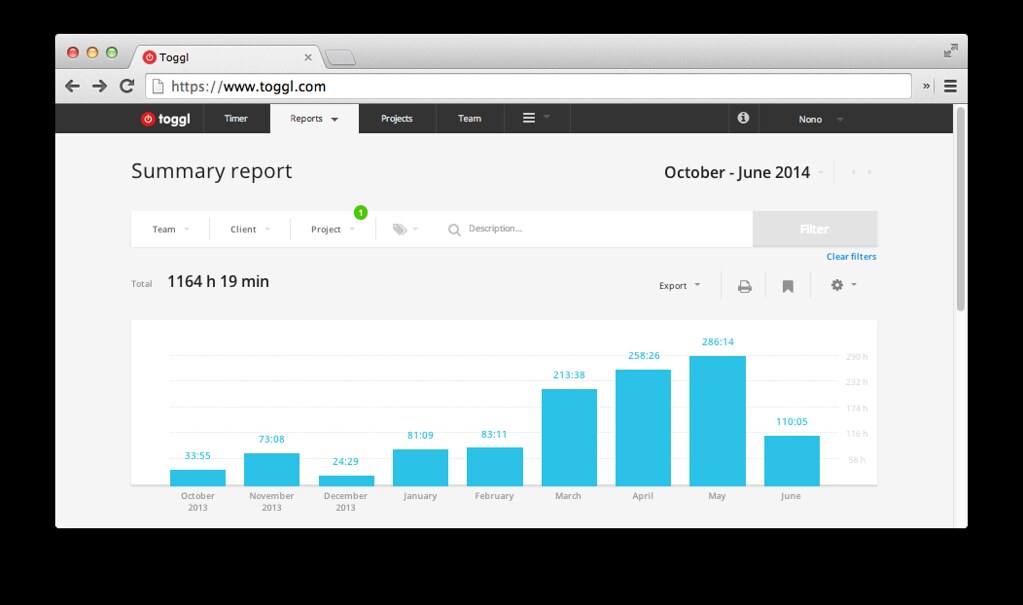

Accounting what you spend your time on is important to value when you are more productive. Knowing at the end of a week if you worked 20 or 70 hours allows you to judge what of your habits are good to get focused, or what things are taking you out of the game. Track what you do, and then set a minimum of working hours a day in your project.

Here is a graph of the hours I spent working on my final project. It was created with Toggl, a really cool online time-tracking service, available for free.

Lay everything you have to do out, sketch how it will look and imagine that it is already finished. How does it look like? What does that finished thing have that you did not think you had to do?

Kike and I started laying out our project's boards when we started producing work, rather than when we were finished. Setting a place in your formats for the things you have to do clears out what you need to do. This helps to avoid wasting your time doing things that are not needed: if it does not have a spot, I don’t have to do it.

A close deadline helps taking fast decisions, not good ones.

A far away deadline allows for decisions to be postponed until there is a close deadline. Even though this is not always the case, it frequently happens —to me too— as the pressure of a deadline only catches our brain when it is getting closer.

My suggestion here is: Write down a list of needed-decisions far away from the deadline; Start taking quick decisions right away for all of them. Some of your decisions will never change, as there is no need for them to, but others will have the possibility to be judged and evaluated —by you and others who see your project— long before the final submission comes.

Over and over, decisions won't be a blank in your brain, stressing you out every time you remember them, but an action taken which can be judged and improved.

Lastly, I want to say that this three points can be applied to any project you get involved in: Make the hours you work accountable, track your time; Frame the whole thing before getting lost in small details; And do not make each decision an odyssey.

Now, go get it done the best you can. And if you liked this article, please share it with your friends!

This article is part of a series of posts about architectural methods, workflows and tools, titled Getting Architecture Done. If you want to be notified when any other articles of the same series are posted, go ahead an subscribe here.